Harold Hill was in a car in Austin, Texas on Nov. 22, 1963, as a member of the communications crew setting up for President John F. Kennedy’s next stop after Dallas.

Shortly after 12:30 p.m., at the window, a sharp rap. Two strangers had spotted the White House sticker on the windshield.

“Did you know the President got shot,” the men asked?

Hill and crew did not believe it.

“Yeah, sure,” Hill said.

Shortly after that, two other men came along, talking to each other about the shooting, and Hill and his crew realized the terrible truth.

Hill, a former Auburn and Kent resident, and a longtime member of First United Methodist Church in Auburn, died at St. Francis Hospital in Federal Way on April 6 at age 87. The couple had seven children: Howard, Nancy, Doug, Anita, Patrick, Ellen and Larry.

He was buried in a Kent cemetery on April 11. His memorial service is at 1 p.m. on Saturday, May 19 at the First United Methodist Church in Auburn.

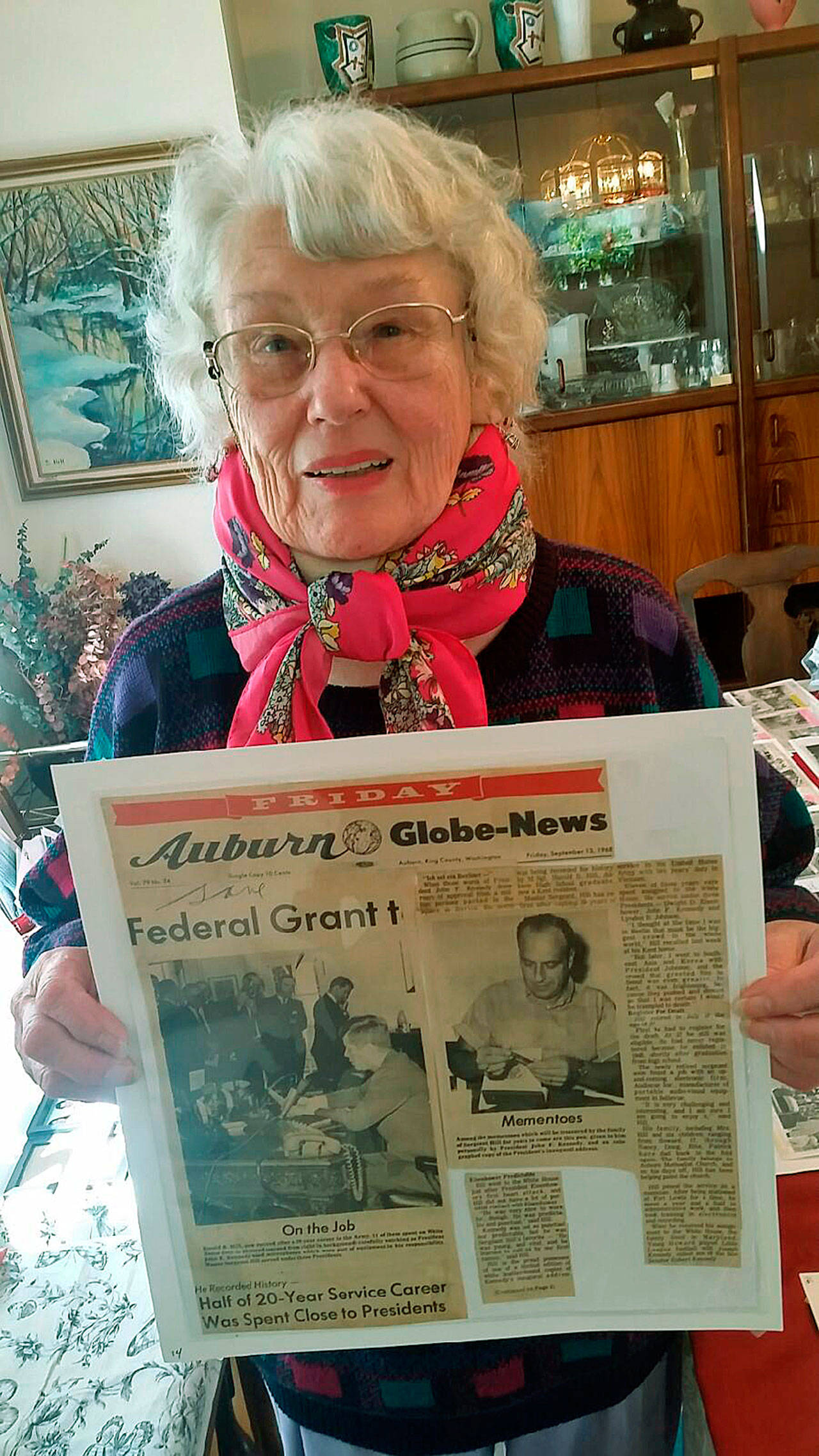

Today, the dining room table in the home Hill shared with Sylvia, his wife of nearly 68 years, in Tacoma, is laid with photographs and mementos of his long, rich life, all of which his wife will share at the memorial service.

Hill in the 71st Army Band barracks at Fort Clayton in Panama.

Hill training in Panama, where he learned to exist for days in the jungle and eat bugs.

The couple’s first car in Panama, their postage stamp of an apartment, their dinky kitchen,their children; a newspaper photo of JFK at his desk signing a document in the Oval Office, Hill among a group of men in the background.

In the living room, one of Eisenhower’s paintings, which became a presidential postcard.

Harold met Sylvia in geometry class at Auburn High School. He, a year her senior, sat behind her, and, she couldn’t help notice, began finding his way into her classes. Turns out, he knew how to make her laugh, too.

“A smartass,” Sylvia said with a laugh.

Upon Hill’s graduation from AHS in 1948, a representative of the Army Band at Madigan recruited the trumpet-playing youth into the band, along with two other young musicians.

Silvia graduated a year later.

When the Army sent Hill to Panama in 1949, Sylvia began college in Ellensburg. But in June of 1950 he returned to marry her, in a night ceremony lit by flashlights in her back yard. The couple went on to Panama, where they spent the first four years of their married life, and where their first two children were born.

After four years, Hill was reassigned to Fort Huachuca, Ariz. Later, the Army sent him to New Jersey and then on to Fort Meyer, Va. near Washington, D.C.

When sinus trouble forced Hill to give up the band – he was one of those people who could, and did, play every instrument that came to his hand – he retrained in recording and electronics and went looking for a job at the Pentagon.

Shortly after President Eisenhower’s first heart attack, the Army assigned Hill to the White House as a communications and recording specialist. His job then, and after, would be to record every public utterance of the president.

While Hill did not have a lot of personal contact with “Ike,” Sylvia said, her husband found him predictable and punctual, always Army, and always “The General.” And he thought the world of First Lady Mamie Eisenhower.

Of the three presidents Hill served in his 11 years in the White House, however, Kennedy was his favorite, and he always carried a special place in his heart for him.

While he found Kennedy not as predictable as Eisenhower, he was personable, informal and approachable. The president and Jackie invited the children of Hill and other staff members to participate in the annual Easter Egg hunts on the White House lawn. He played softball with Joseph Kennedy II, the oldest son of Robert Kennedy.

The president presented him a rare, white leather-bound copy of his 1961 Inaugural Address.

And when Kennedy delivered his famous “Ich bin ein Berliner” speech in West Germany in 1963, Major Sgt. Harold B. Hill was there to record it for posterity.

“I thought at the time I was in Berlin it must have been the biggest crowd in the whole world,” Hill told the Auburn Globe upon his retirement from the Army on Sept. 13, 1968. “But later, I went to Southeast Asia and Korea with President Johnson, and the crowd that greeted him in Seoul was even greater. In fact, I was frightened because they pushed and shoved so that I was certain I would be trampled to death.”

In the article, Hill reminisced about JFK.

“He was young and vital, and learned to call us by our first names,” Hill said.

After Kennedy’s assassination, the communications crew in Austin had to return to Dallas to pack everything up, and then make their way to LBJ’s ranch and install the communications apparatus to link the ranch with the world.

“Johnson was on a 29-farmer line to the ranch, that was it. They had to put in new communication lines out to the ranch, so they were out digging ditches. Same thing when Eisenhower went in, they had to dig ditches and stuff to get lines to the Eisenhower farm. When presidents go on vacation, they’ve got to have secured communications there,” Sylvia said.

Hill’s last act for the late president was to record his funeral, at the special request of Jackie Kennedy.

“Jackie wanted him to record the procession, everything from the cathedral to the gravesite, so he had to get men stationed along there, and they leapfrogged the parade and recorded anything that happened along the way and took pictures,” Sylvia said.

“I had our kids up on top of the hill above the burial site. You couldn’t see anything but the procession from there, but there were crowds up there. It was all wbroadcast on loudspeakers. I took a couple of neighbor kids along with mine. There was a big cross, 8-foot tall and made of granite. My boy and another boy climbed up on the arms of the cross. I decided, ‘I don’t know those kids.’ They wouldn’t budge, so there they were, looking disrespectful,” Sylvia said.

Hill found President Lyndon Johnson much more aloof and distant, or, as he told Sylvia, a “big blowhard.”

Sgt. Hill served one year of active duty in Vietnam.

After his retirement, he found a job with an up-and-coming electronics firm, AUDISCAN Inc., a manufacturer of portable, audio-visual equipment in Bellevue.

When he passed, Sylvia said, the world lost someone special.

“He was someone who was earnest about everything, gave his best, always worked hard,” Silvia said of her late husband. “From our children, I’m learning how much fun he was. I forgot that he played with the kids – he got grumpy when he got older.”