It was a lost battle in The Forgotten War.

Yet Auburn’s Larry Doll remembers the horrific, frontline firefight all too well. Even now, more than 60 years later, he struggles to describe the carnage.

“The 6th crack division of North Koreans was there, and they just sucked us into a tunnel,” Doll recalled of the fierce battle played out on the Korean Peninsula on July 27, 1950. “It was (hell). … It was an ambush.”

Doll – a wide-eyed, frightened teen in the U.S. Army infantry – somehow survived the skirmish and fought his way out of the South Korean village. Many of his buddies did not.

Historically, the Hadong Ambush is a neglected footnote in the early chapters of the Korean War.

Unprepared for combat, American forces – specifically the Army’s undermanned 3rd Battalion, 29th Infantry Regimen – were pinned by North Korean crossfire and decimated in the three-hour battle. North Korean forces were able to divide the American force and kill most of its commanders, further disorganizing the men.

When the shooting and shouting ended, the 29th ceased to exist. The firefight left 313 U.S. soldiers dead, 135 wounded and 100 captured. Only 354 members of the battalion, including some walking wounded, were able to report for duty the next day.

It was the war’s second-worst single-action loss for GIs.

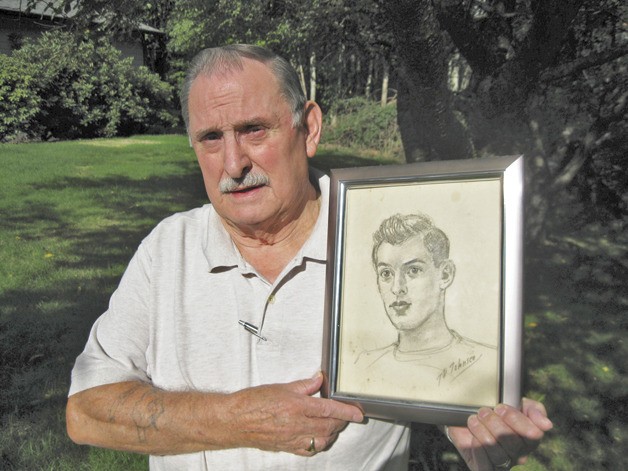

The defeat staggers Doll, 78, one of the 65-or-so known living survivors today of that ambush.

“I think a lot about it,” he said, pausing to hold back the tears. “So many boys … “

Doll is grateful to have survived the war. He would come home, raise a family, build a successful managerial career in the parts and paint supply business and enjoy a quiet, active retirement with his wife, Cyndy. Outgoing and friendly, he is a VFW member and enjoys sharing time with friends at the Auburn Senior Activity Center.

As America honors service members and veterans for their duty and sacrifice this month, Doll will pause and reflect. He says he feels fortunate and blessed to be living today.

“Every day I thank God I got out of there,” he said. “I’m not an overly religious person, but … “

Born in Aberdeen and raised primarily in Northern California, Doll forged his mother’s name and joined a buddy to enlist in the Army. He sought a trade, an education in the Army, but what the innocent and naive teenager got was an abrupt, intense transformation into a hardened soldier.

“I was a boy,” Doll said. “I came back this man.”

He was a survivor, not a hero.

Equipped with a 15-pound BAR (Browning Automatic Rifle), Doll was with one of the first units to enter the Korean theater. The freshly installed and inexperienced 29th was sent in to prevent a major enemy advance from taking the vital south port of Pusan.

They had no idea what they were stepping into.

“We got there and we thought, ‘We’re taking care of this real quick,’ ” Doll recalled.

But the civilians knew different.

“They knew more than we did,” Doll said. “They said a lot of you boys are not coming back.”

Following the failed mission came the chaotic withdrawal, leading to hundreds of casualties.

“It was sad,” Doll said of the ambush. “We had our pants (down) to our knees. We were very unprepared.”

Destroyed after its first engagement, the 29th Infantry was disbanded and merged with other units as the North Korean forces advanced and attacked U.S. positions to the east.

Push to China

Doll stayed in the fight, joining other outfits in the allies’ eventual push up the peninsula to the Yalu River and the Manchurian border.

The prolonged fighting left a weary Doll pessimistic.

“I knew I wasn’t coming home,” he said. “It was just like a blank wall. They were killing us every day. You prayed every time you put your foot down, let me tell you.”

U.S. forces eventually were forced to retreat as Chinese Communists joined North Koreans to launch a successful counterattack in November 1950.

After months of heavy fighting, the center of the conflict was returned to the 38th parallel, where it remained for the rest of the war.

Doll was wounded in action, struck in the leg by a Chinese burp gun, and discharged. He came home in early 1951.

At war, Doll witnessed its ravages and the emotional toll. He vividly recalls one of his first encounters with an enemy solider.

“When he come at me, I thought to myself, ‘Why can’t I just walk up and shake hands with him?’ He looked as if he didn’t want to be there, either. He looked like he was 10 years old.”

Doll was a young soldier, fearful but focused to do his duty.

“It was a job,” he said. “It’s what we had to do.”

Wedged between World War II and the Vietnam War, the Korean War goes largely unnoticed.

Doll understands this.

“You were proud to be an American to be there. You thought it was your duty until later on, politics started coming in,” Doll said.

Many Korean veterans returned home to indifference.

While recovering from his wounds at the Madigan Army Medical Center, Doll went out for coffee and pie at a nearby spot. A man approached Doll, who was dressed in full uniform, his leg in a cast.

“He asked me, ‘Did you break your leg skiing?’ ” Doll recalled.

Over time, the country has grown to recognize The Forgotten War and honor those men and women who were a part of it.

About 122,000 Washington soldiers served in Korea, 532 of them were killed.

A Korean War memorial has been established in Olympia. Other memorials have been created in other cities.

The war should not be forgotten, Doll insisted. And the man of today hasn’t forgotten the many teenagers of the past who bravely fought and lost their lives.

“We served and for some of us, survived it,” he said. “Every new day is one that has been extended to me. I am truly thankful for that.”