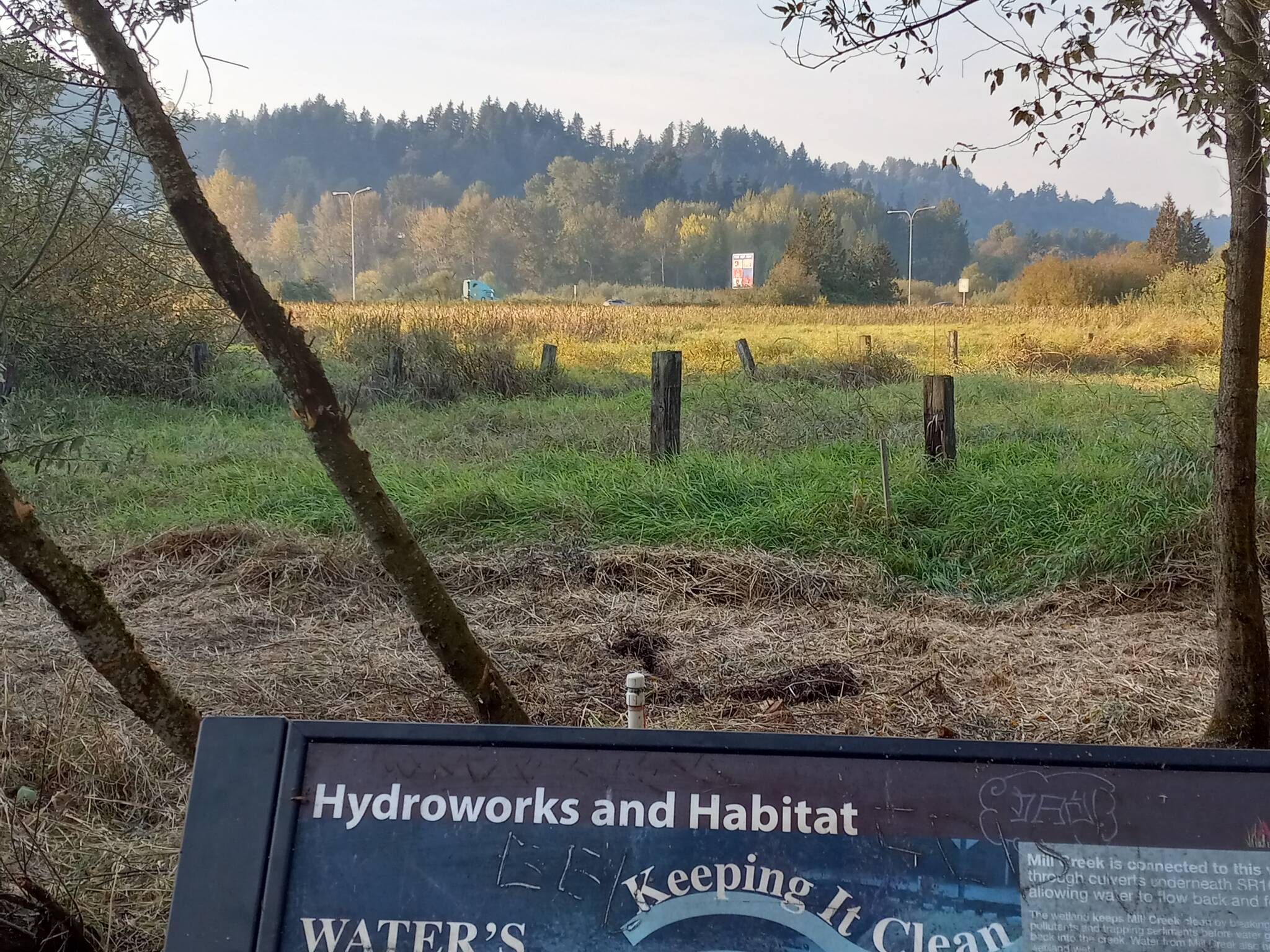

When Auburn developed Phase 1 of the Environmental Park more than 12 years ago, city leaders foresaw a second stage, when it would extend the present western boundary through wetlands to West Valley Highway.

But in deference to other, higher-priority needs within the community, Auburn officials have since continued to push that second phase into the future — although it has the property to complete capital projects there, including additional boardwalk.

“I don’t see the future second phase of the boardwalk out-competing such pressing issues as homelessness, public safety or human services anytime soon,” Community Development Director Jeff Tate said recently. “So, I wouldn’t say that the plans are dead, but they are certainly taking a long nap.”

It’s an issue of funding priorities, Tate emphasized, not connected to the city council’s elimination of the Environmental Park zoning designation after the zoning had failed to attract the sort of green business-friendly development the city had hoped for.

For the sake of clarity, the zoning went, but the environmental park is still there.

“The naming of the Auburn Environmental Park and the Environmental Park zoning designation were always confusing, even to people inside City Hall,” said Tate. “They were really two different things, two concepts that happened to reside right next to each other.”

So, someday, but no time soon.

Yet, whenever the city does move forward, Phase 2 is likely to smack up against a recent reality: the sometime presence of homeless people in the park.

According to Auburn’s camping ordinance, if the city offers services to homeless people found camping on city property in places where the practice is not allowed, and those people refuse to take advantage of the services or go into a shelter within 48 hours, the city can trespass or even arrest them.

While the city has trespassed individuals, to date it has not arrested anyone who has fallen afoul of the ordinance, said Kent Hay, the city’s homeless outreach coordinator.

“When it comes to the environmental properties, it has been challenging,” Hay said. “We still have to play by the rules laid down by the Boise ruling, even in the wetlands. I think we’ve done a good job, though, of applying the 48-hour notice of trespassing people from those properties and cleaning them up.”

What the Boise decision says is that a city cannot simply tell an individual to “move along” from, say, a sidewalk, without offering that individual shelter — in Auburn’s case, within 20 miles — and arranging for transportation there.

Hays noted that he does not expect an overabundance of problems in the environmental park, though issues remain.

“I tell people it’s really like a prison out there,” Hay said in general of homeless encampments. “It’s the same as when I worked at Monroe Prison, except there are no guards. It’s not just people trying to live. People should just stop saying that. It’s really anarchy. There are no rules.

“Now that drugs are pretty much legal, we have behaviors that are escalating. A person off a trail that hit another person with a machete and almost cut his fingers off. It’s street justice,” Hay said.

Problems, Hays, added, are especially acute in areas under county control, such as in the riparian areas east of Brannan Park, where there are extensive homeless encampments and the city has no jurisdiction.