The day is Christmas Eve — the setting, Avalon Care Center in Federal Way.

In a bed in Room 211 an 81-year-old man fights for each breath, but his heart is dying, his body filling with fluid.

We, his children, grandchildren and assorted wives and husbands, have come to be with Maurice G. Whale on this last night as himself.

We dust off the well-worn family tales and tell stories about the man in the bed that even my brother-in-law hasn’t heard. We cry and laugh by turns.

Over the course of that long day, each approaches to talk in the old man’s ears.

“Pop, we’re all here” … “Can you hear me?” … “I love you.”

As the shadows lengthen, the breathing grows more shallow.

“You’re working hard for each breath aren’t you, pop?” my brother says.

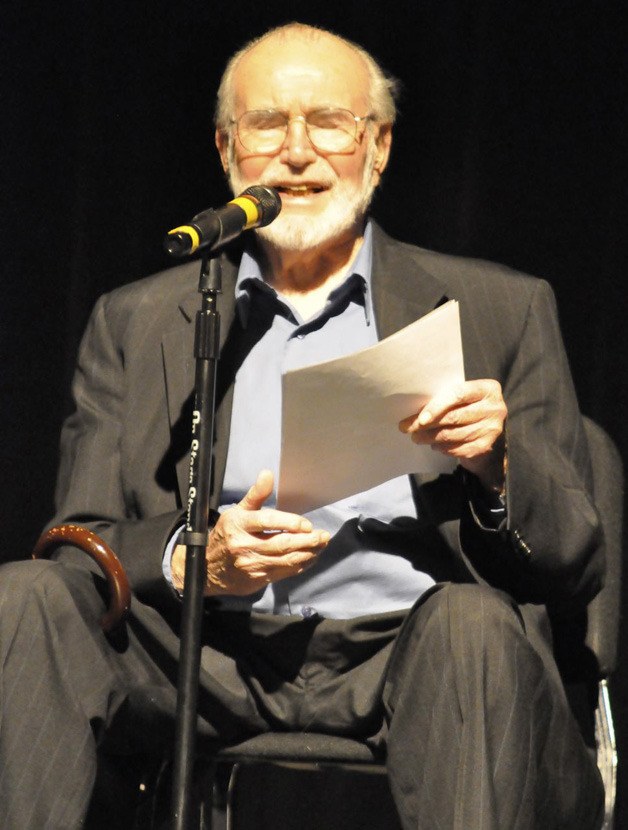

As I look down on the white hairs and beard, the hands turned wine-dark by medication, the stick-thin legs, the whole man diminished from his days of vitality, a thousand memories of sunnier times crowd the mind.

Of endless summer nights, dad’s pancakes on vacations to the Oregon coast, early evening dips in the Green River, visits to Lake Surprise, quiet moments just talking.

Photos from the family album flicker on an internal screen: a small black-and-white of dad smiling in a washtub on a fire escape in his native Queens, N.Y.,; my mother, she, so beautiful, he, so handsome and cocky in his Coast Guard blues, standing in front of the Burlingame Hotel in Seattle, when everything was young and life lay before them.

And just look at that cat-who-swallowed-the-canary grin on his face as he stands at the altar with my mother. What was he thinking about?

As the years roll on, there’s Dad and Mom with all six of us kids. An Auburn Globe article, “Daddy gets degree,” featured the whole family in June, 1963, during a busy week when he earned his electrical engineering degree and my little sister, Diane, was born. I, described in the photo cutline as “curly-haired Robert,” sit in his lap.

There are hard things to remember, too.

On the night my brother, Jim, died, how he roared, “Oh, no!” as my mother broke the news. Then the wrenching sobs: “O, ‘Rene, our boy isn’t coming home anymore!”

Then there was the Sunday morning when my mother died. Dad and I were with her. He recited from the Book of Common Prayer.

Snapshots of the life ending.

About midnight my brother in law brings a guitar, and my brother, Matt, begins to play. We sing some of dad’s favorites.

Like everybody else on the planet, my dad was a mixture. He yelled a lot. He said hard things I’m sure he swore he would never say, having heard them from his own father.

But my father also left singular gifts for his children.

He was the one whose playing inspired his children to pick up the guitar.

I think what he passed to me was his odd way of looking at the world, a mixture of pessimism and a keen sense of the sublimely ridiculous. Also his love of words. He always will be there in my mind, singing snatches of W.S. Gilbert’s “Bab Ballads,” reciting from “The Rubaiyat.” quoting Rudyard Kipling’s “Gunga Din.” These things live in my bones.

It is now Christmas day. About 2 a.m. I leave to get some sleep. Shortly afterward my brother, Jack, calls to tell me of dad’s passing. It came so softly, he said, that nobody knew for a moment that his breathing had ceased. For this I am grateful. I remember Samuel Johnson’s moving poem on the death of his friend, Robert Levet.

“Then with no throbbing fiery pain …

Death broke at once the vital chain …

and freed his soul the nearest way.”

So long, pop. I’ll miss you, ol’ fella.